Our coordinator, Dr Nuno Cardoso-Ribeiro, was quoted and made statements to the Público newspaper about Generation X marriages, particularly with regard to spousal inheritance and joint assets.

Read the article on Público’s website or the translation and in pdf below:

"Generation X is only now getting married. Inheritance and wealth help explain why

Monday, 3 October 2022. The day dawned warm and would have been just another day on the calendar, had it not been for Mariana Cruz’s 45th birthday and also the day she chose to marry Mário Marques, the man she had shared her life with for almost 30 years. Aida Graça and Fausto Santos also chose to get married after turning 40 and after many years of living together. Marta and Artur (fictitious names) did the same. Because they did, because an old family alliance was rediscovered, but above all because, in legal terms, a de facto union is not the same as marriage, especially when it comes to property and inheritance.

These three couples belong to Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980) and it was with and for them that Portuguese society began to look through a magnifying glass less laden with prejudice: they were the first generation for whom marriage didn’t necessarily have to precede the sharing of a common home, a life, the creation of a family (https://www.publico.pt/2023/01/24/sociedade/noticia/familia-nao-crise-apenas-reinventarse-monoparentais-recompostas-aumentaram- 2036243). Now, however, many are deciding to formalise their situation. There are many reasons for this, and they mainly concern legal security issues, particularly regarding assets and inheritance, but also peer pressure or purely ideological reasons. PÚBLICO spoke to three couples who, as the years went by, found themselves motivated to pick up the pen and say “yes”.

Since the age of 17, when she started dating Mário (a civil engineer on major construction projects), Mariana (a businesswoman in the industrial sector) has kept “her wedding ring in her heart and head”. “I don’t need a ring anywhere else,” she argued several times in response to the question: “So you’re not married?” In the case of Aida and Fausto, there were times when they considered themselves “anti-marriage”. Marta, on the other hand, never disdained to see a bouquet in her hand. And she confesses that she waited three decades for the proposal. “It’s the man’s job. I had this dream of entering the church dressed in white. We’re also Catholic, so I thought I needed to get married for religious reasons,” she reveals.

From a dream to a contract

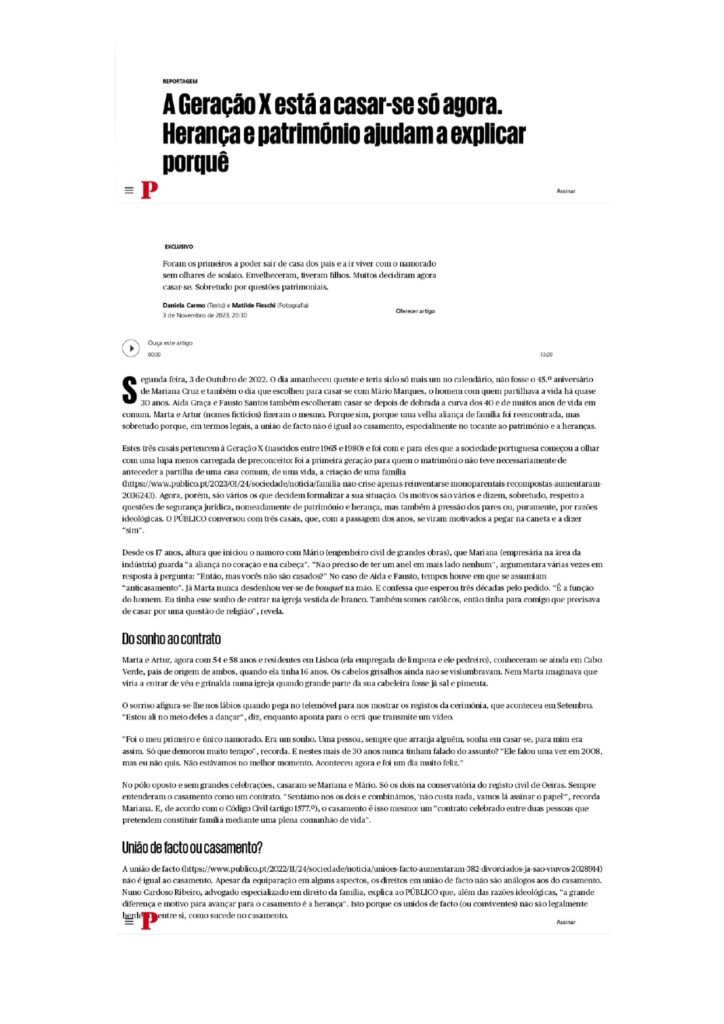

Marta and Artur, now 54 and 58 and living in Lisbon (she as a cleaner and he as a bricklayer), met in Cape Verde, their country of origin, when she was 16. Their grey hair was not yet visible. Nor did Marta imagine that she would enter a church wearing a veil and garland when much of her hair was already salt and pepper.

A smile appears on her lips as she takes out her mobile phone to show us the records of the ceremony, which took place in September. “I’m there in the middle of them dancing,” she says, as she points to the screen transmitting a video.

“He was my first and only boyfriend. He was a dream. Whenever you get someone, you dream of getting married, and that’s how it was for me. It just took a long time,” she recalls. And in more than 30 years they’d never talked about it? “He mentioned it once in 2008, but I didn’t want to. We weren’t at the best moment. It happened now and it was a very happy day.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum, and without much celebration, Mariana and Mário got married. Just the two of them at the civil registry office in Oeiras. They always understood marriage as a contract. “We both sat down and agreed, ‘it’s no trouble, let’s go and sign the paper’,” recalls Mariana. And according to the Civil Code (Article 1577), marriage is just that: a “contract entered into between two people who intend to start a family through a full communion of life”.

Civil partnership or marriage?

A civil partnership (https://www.publico.pt/2022/11/24/sociedade/noticia/unioes-facto-aumentaram-382-divorciados-ja-sao-viuvos-2028914) is not the same as a marriage. Despite being similar in some respects, the rights of a civil partnership are not analogous to those of marriage. Nuno Cardoso Ribeiro, a lawyer specialising in family law, explains to PÚBLICO that, apart from ideological reasons, “the big difference and reason to move towards marriage is inheritance”. This is because unmarried couples (or cohabitants) are not legally heirs to each other, as is the case with marriage.

“This happens when, in effect, the cohabitants want to safeguard the effects of inheritance. In other words, they want their partner to be their heir,” explains the lawyer. A member of a civil partnership “will only inherit if they are a testamentary heir or legatee”. This means that there must be a will in their favour made by the deceased cohabitant.

A practical example: the civil partners buy a house, which remains in the name of only one of them. If one of them dies, the surviving cohabitant will only inherit if there is a will in their favour. But it has to be “a will that respects the reserved rights of the legitimate heirs”.

This category of legitimate heirs corresponds to those who cannot be disinherited, including children. “This means that a will that violates this reserved portion, this right of the children, will not be applicable in this part. So let’s say the house is the deceased’s only asset. By means of a will, he could not validly assign it only to the surviving cohabitant,” explains Nuno Cardoso Ribeiro.

It was also to safeguard the future (https://www.publico.pt/2021/04/07/p3/noticia/regras-amor-uniao-facto-casamento-descobre- diferencas-1957050) that Mariana and Mário signed the paper, although they are not in any situation similar to the one described above. The marriage took shape when, in the midst of tidying up, Mariana’s father found her mother’s old wedding ring, as well as other belongings. And that was the ring that Mariana wore after she was married.

What if...

Sitting at the living room table, Mariana unravels the story: “I had a very strong bond with my grandmother, my father’s mother. And around that time, there was a news story about a lady who had lived with a man for 27 years of her life. In the last six years of living together, the man had terminal cancer and she was the one who looked after him. She stopped working and lived in his house. But you never made a will. When you died, she was thrown out. At the age of 50-something, she was left without a job, without a home and with one hand in front of her and the other behind.”

It was then that she looked at Mario, whom she was already calling her husband, and said:

– We don’t have any situation like this. But imagine something happening?

The house, the third in which they live, is their own and is in both their names; they both have assets. “We’re not alone,” he thought. “But,” there was always an adversative. In conversations with friends, they realised that, after all, “being married and being de facto united are not the same thing”.

Apart from that, getting married was “very easy”. “I never thought it would be so simple. It was a civil marriage and you don’t even need witnesses.” The pair chose to start the marriage process online. “I was sitting here and he receives an email saying: ‘So-and-so wants to marry you on 3 October at 10am. If you accept, please confirm here. I thought it was amazing.”

The choice of day was not innocent. “It was my birthday, so there’s no forgetting the date,” she laughs. The birthday party is already a tradition and 2022 would be no exception. With friends and family gathered, dinner was the time of day chosen to announce their marriage. Her sons, Duarte and Vicente, were already aware, as was Mariana’s father. And in the meantime, a few more people joined them. But that didn’t mean the day was out of the ordinary: “We went about our normal lives, in the evening we went to the gym, everything was very normal, except that we signed the paper.”

Marriages with a prior common residence have increased

To PÚBLICO, sociologist and president of the Portuguese Demographic Association, Paulo Machado (https://www.publico.pt/autor/paulo- machado), recalls that there are no statistics that tell us how many couples are in this situation, i.e. who decide to formalise their relationship after years in a de facto union. “The data we have from the declarations doesn’t tell us how long people have been living together. But it is possible to know if the children of unmarried parents already had their parents together when they were born,” he explains.

The data published by the National Statistics Institute (INE) allows us to measure, for example, the number of marriages with previous common children: in 2022, out of a total of more than 36,000 marriages, 10,165 were of couples with previous common children; in 2018 this share was 8532 couples. Another indicator is the rise in the average age of men and women at first marriage: in 2022, it stood at 35.1 years for men and 33.7 for women; in 2018, these figures were 33.6 and 32.1 years, respectively.

Almost 70% will live together before getting married

In the case of couples with a common previous residence, we know that this percentage has been increasing. While in 2018 this universe represented 59.8 per cent of all couples, by 2022 this figure had risen to 68.5 per cent, in other words, an increase of almost nine percentage points.

There are, however, several clues that explain the tendency “for people who have been in a de facto union for many years to formally enter into marriage”, starting with questions of legal security, particularly with regard to inheritance. “If there is widowhood, for example, safeguarding the rights of people living in a de facto union is always more difficult. People realise that, when it becomes important at a certain stage in their lives, they consider it and do it, in other words, they end up legally consolidating the relationship they had,” says the sociologist.

On the other hand, there is also social pressure. “Marriage has not lost its value in society,” emphasises Paulo Machado. “In sociology there is what we call conformity, in other words, it’s a conduct, a behaviour that stems from an attitude, from a certain idea (which is a social thing) of social conformity.” This means that individuals end up acting in the way their peers expect them to. “It’s a question of great importance that has to do with this social regularity, meeting what is expected of us.”

More holidays

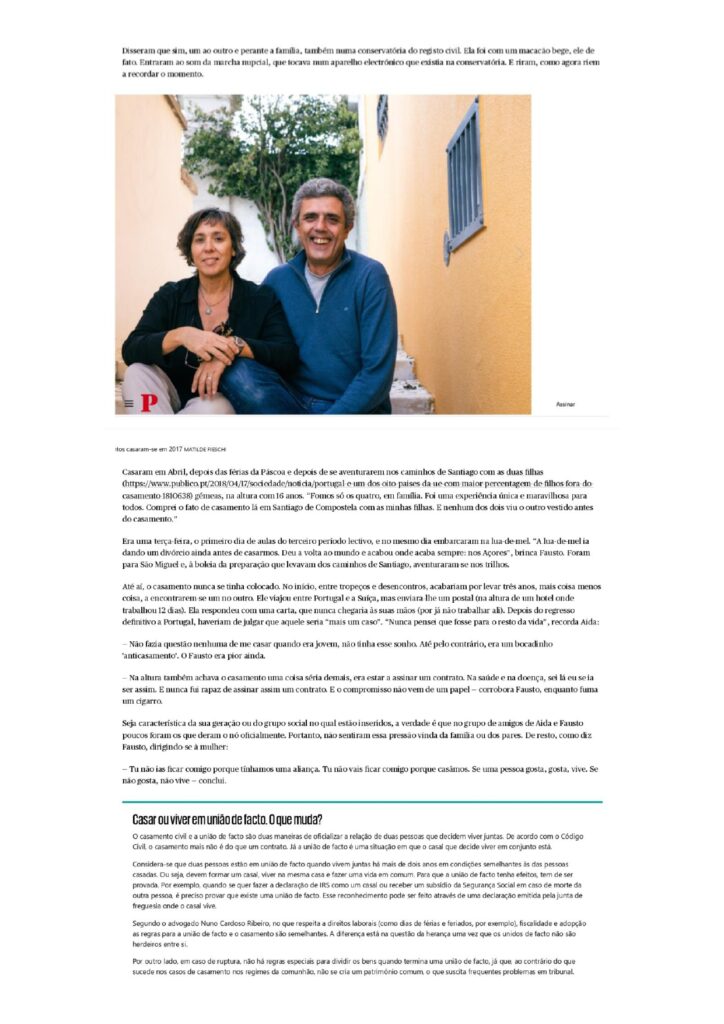

Consciously, Aida and Fausto (53 and 54) don’t feel any pressure to get married.

We arranged to meet them on a terrace in the centre of Palmela so they could tell us their story. We see the two figures walking towards us, with relaxed steps and broad smiles, and that’s how they recall the encounters and disagreements that led up to their wedding.

They were civilly married in 2017, the year they celebrated 25 years together. What began as a “joke” to mark the date, became a reality thanks to the fact that they were given 15 days of marriage leave, which had to be taken consecutively.

They said yes, to each other and in front of their families, also at a registry office. She went in a beige jumpsuit, he in a suit. They entered to the sound of the wedding march playing on an electronic device in the registry office. And they laughed, as they do now, remembering the moment.

They got married in April, after the Easter holidays and after venturing out on the roads to Santiago with their twin daughters (https://www.publico.pt/2018/04/17/sociedade/noticia/portugal-e-um-dos-oito-paises-da-ue-com-maior-percentagem-de-filhos-fora-do- marriage-1810638), who were 16 at the time. “It was just the four of us, as a family. It was a unique and marvellous experience for everyone. I bought the wedding suit there in Santiago de Compostela with my daughters. And neither of them saw the other dress before the wedding.”

It was a Tuesday, the first day of classes for the third term, and on the same day they embarked on their honeymoon. “The honeymoon was going to lead to a divorce before we got married. It went round the world and ended up where it always does: in the Azores,” jokes Fausto. They went to São Miguel and, hitchhiking on the preparation they had taken from the roads to Santiago, ventured out on the trails.

Until then, marriage had never come up. In the beginning, between stumbles and misunderstandings, it took them three years, more or less, to find each other. He travelled between Portugal and Switzerland, but sent her a postcard (at the time from a hotel where he had worked for 12 days). She replied with a letter, which never reached him (as she no longer worked there). After her definitive return to Portugal, they would have judged that to be “just another case”. “I never thought it would be for the rest of my life,” recalls Aida:

– I didn’t want to get married when I was young, I didn’t have that dream. On the contrary, he was a bit of an ‘antic’. Fausto was even worse.

– At the time I also thought marriage was too serious, it was signing a contract. In sickness and in health, I don’t know if I was going to be like that. And I’ve never been one to sign a contract like that. And commitment doesn’t come from a piece of paper,” says Fausto, while smoking a cigarette.

Whether it’s a characteristic of their generation or of the social group they belong to, the truth is that few of Aida and Fausto’s group of friends have officially tied the knot. Therefore, they didn’t feel this pressure from family or peers. Besides, as Fausto says to his wife:

– You weren’t going to stay with me because we had an alliance. You’re not staying with me because we got married. If you like it, you like it, you live it. If you don’t like it, don’t live it – he concludes.

Marrying or living in a civil partnership. What changes?

Civil marriages and civil partnerships are two ways to formalize the relationship between two people who decide to live together. According to the Civil Code, marriage is nothing more than a contract. On the other hand, a civil partnership is the situation in which a couple who decides to live together is in.

Two people are considered to be in a civil partnership when they have lived together for more than two years under conditions similar to those of married people. In other words, they must form a couple, live in the same house, and lead a common life. To have legal effects, a civil partnership must be proven. For example, when one wants to file income tax as a couple or receive a social security allowance in the event of the other person’s death, it is necessary to prove the existence of a civil partnership. This recognition can be obtained through a declaration issued by the local parish council where the couple resides.

According to lawyer Nuno Cardoso Ribeiro, with respect to labor rights (such as vacation days and holidays, for example), taxation, and adoption, the rules for a civil partnership and a marriage are similar. The difference lies in the matter of inheritance since civil partners are not heirs to each other.

On the other hand, in case of a breakup, there are no special rules for dividing assets when a civil partnership ends because, unlike a marriage celebrated under community property regimes, no common estate is created, which often leads to legal problems.”